You should have a normal life expectancy. This sentence rang in our ears as we left Dr. B's office this morning.

First Dr. B's PA — let's call her Ms. X — entered. No smiles here, but on the other hand, a daunting air of capability. Straight to business:

any chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness? Nausea or vomiting? Then a quick physical exam, then she left to discuss with Dr. B.

One thing I learned from

House — an easy character to hate, but one who's usually right — is that I don't really care if my doctors are nice people. I want them to be stunningly, overwhelmingly competent (at least so long as that doesn't stop them from really listening). If they also happen to be nice people, yahoo, but that's gravy. If they need to be arrogant or abrasive to get that edge, that's OK with me.

Dr. B entered a few minutes later.

Up on the table please,

then we'll chat. He asked me all the same questions Ms. X had just gone over. Then he did the exact same physical exam, hunting for my spleen, which none of the doctors have been able to palpate even though it's enlarged. Dr. B couldn't feel it either, but he knew how to try. I was thinking

why is he repeating everything his PA just did? Then it dawned on me:

error-checking.

Obsession with detail. Need to know from own experience, not just report.I sat down beside Gabrielle. Dr. B perched on the exam table, began twiddling a paper towel. And launched into a mini-lecture on hairy cell leukemia that could have come from a textbook, except it couldn't, because he knows the insider details no textbook tells. For example: the Scripps studies of

minimal residual disease in HCL always find it (MRD), because they do the bone marrow biopsies just one month after chemo ends. But indolent cancers like HCL take longer than that to clear. Dr. B doesn't do biopsies for MRD in HCL until 3 months. As for MD Anderson,

things always work better in Houston. The Northwestern team takes the same approach as Dr. B, who knows this because he's talked it over with the head guy. This little talk went on for at least 25 minutes: precise, detailed, tightly organized, perfectly clear. Completely convincing. He answered every question I'd written down before I could ask.

He knew every study I'd read, cited them. Knew my case history cold, including previous conversations with Dr. A about my diagnosis. Knew my blood counts, not just today's but over the last couple of weeks. After hours of poring over papers on HCL diagnostic pathology, I'd decided my HCL diagnosis was correct. Dr. B repeated the chain of reasoning I'd followed. Being fully convinced of this is an enormous relief, because if you have to get cancer, HCL's the one you want. I just read an entire special issue on HCL in

Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America (Oct. 2006), which says that this disease deserves the disproportionate attention it gets

because they are so close to a complete understanding —

and a cure. That last word's not one you hear often in cancer research.

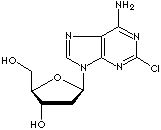

As for long-term

CD4 T-cell suppression following 2-CdA, Dr. B explained why this doesn't translate into clinical immunosuppression. Many immune cells hide in the lymph nodes, the spleen, elsewhere. So low numbers of

circulating cells, the kind detectable in blood tests, don't necessarily correlate with an insufficient supply.

I brought up rituxin and BL22. Dr. B knew all about them. BL22's not ready for prime time; it can cause kidney failure. Dr. B has actually treated at least one HCL patient with rituxin after 2-CdA, and would do the same for me if my remission isn't good enough. But he thinks the risk/benefit balance argues for awaiting a relapse before adding rituxin to the regimen. If 40-50% of all patients never relapse, why not see if I'm in that group first before drenching my blood with another toxic chemical. That's what I'd concluded too, but I needed to hear it from an expert.

I have never witnessed a more confidence-inspiring performance in my life. Dr. B's a virtuoso, a medical master at the top of his game. When he wrapped it up with

you should have a normal life expectancy, Gabrielle's voice broke. Mine too.

White cells, up slightly, might be starting their rebound. Platelets are recovering fast! The count's up to 120 — it was around 100 at the first blood tests in October, so this is significant. Means I don't have to worry about cuts so much. Also, the spot on my leg turned out to be nothing worse than eczema, not to worry.

But the bad news isn't quite over. My hemoglobin's dropped even further, and may go a bit lower yet. I'm at the blood transfusion borderline (hemoglobin below 8; mine's 8.3). I could get one now if I asked for it. Might buy me a week of higher functioning, take my hemoglobin up to around 10. That would be incredibly nice, since I've been in bed most of the time for nearly 2 weeks. The infection risk from a transfusion is just 1 in 100,000, but there are other risks, such as fever and other complications from an imperfect blood protein match. Dr. B seemed to want to wait a few more days, at least until the next blood test on Thursday. It's easier to track what my body's doing if they don't interfere with it.

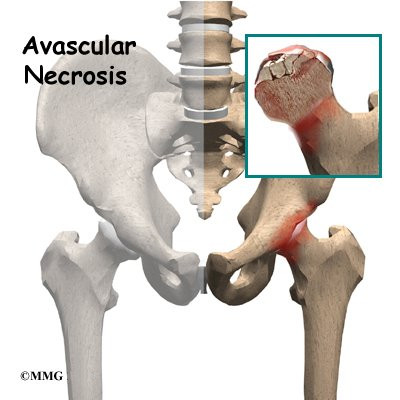

And there's a new issue. My CT scan revealed some kind of problem in the bone marrow of my right femur head and neck, possibly the left one as well. Dr. B thinks it's not the HCL; otherwise we'd have seen the same thing in all my bones. He thinks it's probably avascular necrosis, i.e. bone death from insufficient blood supply. Dr. B sent me downstairs for more X-rays right after our appointment.

Not clear what this means or whether it's serious (yet), though Dr. B did mention hip replacement (but more in a long-term-speculating way). Over the last 6-7 years I've had several episodes of intense muscle spasms in both hips, especially the right hip; this could be related. Maybe connected to 13 years of aikido, which does tend to give your skeleton a pounding.

Still, I haven't had a spasm like that in 2 years, and this problem seems minor compared to cancer. We'll see what the X-rays show.

Came home from the hospital, got into bed and sank into a groggy, horrible sleep until 5:30 PM. And I'm ready to do it again, right now.

I have to say that for me — and not just because of the last three months — 2007 basically sucked.

I have to say that for me — and not just because of the last three months — 2007 basically sucked.